A guide to developing and communicating the right message for your campaign

Communicating the right message is a big part of campaigning for change. An effective message can build understanding of an issue, increase support for your goals and get people involved in taking action. It can also shift people’s politics and values in a deeper way. This guide will help you think about how to develop the right message for your campaign.

This guide is aimed at people who already have some experience campaigning and want to think more about developing a strategic message. It is focused on creating messages that build people’s understanding of the structural power that causes social and ecological injustice. Bringing about long-term radical change requires shifting values in society and successfully countering the narratives of your opponents. Coming up with a messaging strategy can help you plan your outreach with an aim to building power from the bottom up.

Your message is the set of core things you put across as a group or campaign. This could be through your posters and leaflets, outreach conversations or media communications. Your message informs people about the issue you’re fighting, but it also communicates your analysis, values and vision. It’s important to think about what you’re putting across in your message and the effect it will have.

A messaging strategy helps you get clear exactly what you want to put across. It involves thinking about the big picture: what the mainstream narrative is about the issue, what you want the effect of your message to be amongst different people, and how your message builds a vision of the future. Your messaging strategy also fits together with your wider campaign strategy so that the messages you are putting out make the most of your campaign activities.

It’s worth putting time into developing a message that really reflects your analysis and values. This is especially important if you are aiming to shift politics and values in a fundamental way among the people you are reaching. In an unjust world, values of equality, freedom and solidarity are often marginalised. Changing the underlying values emphasised in society is not easy, but it is key to creating more long-term, lasting and radical change.

For example, campaigning for policy changes can improve workers’ rights, but building a society where solidarity is valued makes it more likely that workers are able organise and strengthen these changes. Fighting against factory farming can help improve the food system, but values of equality and sustainability need to be widespread to bring about a world where animals and the planet are not exploited. The tips in this guide assume that shifting values is a necessary long-term aim of campaigning for social and environmental justice. A messaging strategy can help you identify the values you want to build in society and ensure you communicate them in your campaigning.

People often push for small reforms even though they know it won’t change things enough. Often the narratives of our opponents are deeply embedded in society and can be hard to overcome. Those with wealth and power shape the mainstream media and other sources of information that affect people’s understanding of the world. But it is still possible to create powerful counter messages that help people imagine how things could be different and mobilise them to act. One of the things a messaging strategy can help you to do is to say what you really mean, and avoid making arguments that limit your vision or fall into your opponent’s logic.

The diagram below demonstrates the idea of the ‘Overton Window’, or the range of ideas politically acceptable to the mainstream population at any time. Ideas within the window are more likely to be proposed by politicians, given media coverage, and seen as ‘common sense’. The further outside the window an idea is, the less it is currently taken seriously in mainstream discussion about the issue.

The Overton Window is a useful tool to understand the effects of successful political messaging. The idea is that instead of advocating for minor changes to what is already seen as acceptable, making a clear case for the ‘unthinkable’ idea can shift the window of possibility so that ‘radical’ proposals become ‘sensible’ ones.

Having a consistent message repeated using different methods is more likely to make an impact. If you are clear about the core things you want to put across and the effect you want your message to have amongst different people, it can be easily adapted to different situations. A clear, consistent and memorable message is more likely to cut through.

A messaging strategy also helps you think about timing, so that you can make the most of opportunities when your message is likely to have the biggest impact and build momentum.

In order to develop your message it is important to work out your analysis of the issue you want to change. This can help you decide together what to emphasise in your argument, and how to challenge the narrative of your opponents.

Thinking together about the core things you want to get across also helps you get on the same page as a group. It can show how the issue you are tackling impacts people in different ways, and how it might link to other kinds of injustice.

Some helpful questions to think about:

For example:

Get everybody in your campaign group to write down a one-sentence answer to each of the four questions on four post-it notes. Bring everybody’s suggestions together in four columns on the wall and then consider the overlaps and differences in your answers. Work together to synthesise what everybody has said and test agreement.

This helps show how people are affected differently by the issue, or have different priorities for change. It can be a good idea for the whole group to be involved in this process, even if a working group goes on to develop the message framing.

Your analysis also makes clear your values. You understand something to be a problem because it goes against the values you hold – for example by creating inequality, causing suffering or denying people’s freedom. We all hold many different values, but the messages we encounter tap into particular values and emphasise them. Think about the values that need to ‘grow’ in society to move it towards your vision, and try to make these central to your messaging. For example, if you hold equality as a core value you should try to put this across in the message you develop, including the words and images you use.

Think carefully about the emotions you are tapping into with your message. For example, fear can be a strong motivator, but it can also be disempowering. “We only have 5 years to stop climate change!” might spur people into action, but it doesn’t offer a long term vision for climate justice. For sustainable campaigning, helpful emotions are ones that increase both our concern for justice and our feeling of collective power.

To develop a strong message, you need to recognise your opponent’s narrative and make a clear case for your own. This involves challenging assumptions that are built into your opponent’s message, for example about the cause of the problem. If you are countering narratives that are very embedded in society, highlighting the structural power in a situation is a good place to start. Marginalised groups are often scapegoated for problems in society. Making clear the structural cause of injustice directs responsibility back to the system, and to those with power.

It can be tempting to argue back within the terms set by your opponent, but this can actually reinforce their narrative. For example, saying “actually, migrants bring more money into the country than they take” reinforces the idea that migrants should be judged on their economic value. Use your own analysis and values as the starting point when countering your opponent’s message. Highlight the structural power underlying the issue, and offer a vision of how things could be different. Thinking back to the Overton Window, your message can contribute to shifting the window of ideas that are seen as normal and sensible. This can help bring more ‘radical’ ideas into the frame of possibility.

Here are some examples of common narratives that might be used by your opponents, and some examples of counter messages:

| Opponent’s narrative | Example | Your message |

| Not enough to go round: Blaming inequality on a lack of resources. | “Homelessness is going up because there aren’t enough houses to go round.” |

“Housing is increasingly owned by the rich for profit. Houses are homes not assets and should be shared amongst everyone as an unconditional right.” |

| Scapegoating: Putting the blame on a group of people instead of the structural cause of injustice. | “The NHS is struggling because there are too many migrants using it.” | “The NHS has suffered from years of cuts and privatisation. It should be publicly owned and provide free healthcare for everyone who needs it.” |

| False either/or: Pitting two things against each other to imply there is a choice between one or the other. | “The new coal mine is needed to generate hundreds of jobs for local unemployed people.” | “Fossil fuel companies are exploiting workers and causing catastrophic climate change for profit. Building renewable energy would protect the environment and empower workers with well paid jobs for the future.” |

| There is no alternative: Implying that the current system is the best we can have. | “Prisons are the only way to stop people committing crime.” | “Prisons are violent and do not solve the problems in society that lead to harm. We need social and economic justice to prevent harm and deal with problems in our communities.” |

A key step in your messaging strategy is identifying the main people you want to reach. Think about who is likely to take action, and how to emphasise your message differently depending who you’re targeting.

The diagram below is called a ‘spectrum of support’. It’s a tool that helps you to map out where key groups of people are on a spectrum of ‘with us’ or ‘against us’. You can then think about how your message could move these groups of people one wedge to the left, closer to ‘with us’. The spectrum of support helps you prioritise your outreach by identifying who is most likely to take action and focusing your energy there.

Shifting passive supporters into active participants is important because campaigns are usually won through action rather than just changing people’s minds. Another good reason for focusing on increasing active participation is that it can help people see the power they have over their own lives by coming together with others to create change from the bottom up.

Some people may be passive supporters because they agree with your aims but feel disempowered. One of the most damaging narratives in many situations of injustice is that people are powerless to change things. With these passive supporters, ‘countering your opponent’s narrative’ may be about emphasising your collective power. You could talk about victories you’ve had so far in your campaign, or highlight the ways that people getting involved will help push things forward.

You may choose not to spend time trying to win over people who already oppose you. It’s unlikely that your active opponents will be persuaded. However, in our society people affected by injustice are often divided instead of seeing their common interests. Scapegoating offers an easy explanation that hides the structural causes of injustice. This benefits those with power! For this reason it can be worth engaging with opponents to highlight the structural causes of an issue. In this guide we have given some tips about ways of framing your message that emphasise the shared interests people have in creating change, and build the potential for solidarity.

One thing the spectrum of support doesn’t take into account is who is actually affected. This can be a more meaningful question than who supports or opposes you. For example, if you are building a renters union, a reluctant tenant is more important to engage than a sympathetic homeowner. This is also a useful way to decide how to engage with a passive opponent – if they are in the base of people affected by the issue, you might prioritise engaging with them over someone who isn’t.

Who is directly affected is an important political question as well as a strategic one. People’s shared experience of injustice can be a source of knowledge and power. It can provide a fuller understanding of why something is happening and what is needed to change it. Campaigns led by the people directly affected are likely to be stronger for this reason.

Framing is how the words, images and metaphors we choose shape how people see an issue. A message framing can conjure up a whole picture just by using a few words. For example, ‘red tape’ triggers a whole narrative about bureaucratic legislation restricting business. ‘Farming’ might bring to mind images of the countryside and happy animals, whereas ‘factory framing’ conjures up an industrial production line.

When politicians talk about ‘balancing the books’, it immediately creates the image of a national economy that works like a household budget, with the government cutting spending to make ends meet. To understand the power of framing, think about how this language is used to portray austerity policies. Cuts to public services are framed as necessary and responsible actions to ‘reduce the deficit’, instead of political choices.

Frames make some things visible and others hidden. When a certain framing is well-established in society it can become ‘common sense’, so that the associations it conjures up are taken for granted. This means that other ways of seeing the issue seem radical or unrealistic. To take the national economy example, think about how arguments for major investments in public services are seen as far-fetched and met with metaphors like the ‘magic money tree’.

We are always framing things – when you choose one set of words over another you activate certain associations and values instead of others. These can either be helpful or work against your aims. Arguing within the same frame as your opponent can reinforce the same associations even if you’re disagreeing with them. For example, using the metaphor of a “carbon footprint” reinforces the suggestion of individual responsibility for climate change, rather than making visible the social and economic systems that cause it.

Reframing is a way of changing the existing associations and narratives around an issue to emphasise your analysis and values. Your ‘frame’ offers a new way of seeing things. It is generated through metaphors, wording, images and storytelling.

Think back to your analysis and reflect on what you want to emphasise in your reframing of the issue. Consider how you can use metaphors and images that highlight the core parts of your analysis:

Structural power: Issues of injustice are often framed by opponents so that structural power is left out of the picture. Emphasising structural power dynamics can widen the frame so people can see the big picture clearly.

Your own power: What shared experiences or common interests do the people affected have? Using language and images that highlight your own power can help bring people on board, particularly passive supporters who feel disempowered.

Vision: What does the future look like where things are different? This is a good way to put across your values.

As a group, brainstorm the common images and metaphors used around your issue in the mainstream (e.g. in newspapers, TV coverage or political debates). How do these metaphors serve your opponents?

Come up with words and images that frame the issue differently and emphasise your values. Decide on a few you like best, then get feedback from outside the group.

“Property is an investment which people with wealth are entitled to. Landlords who rent houses are providing a service in a fair legal exchange. Some bad tenants don’t pay their rent, and bad housing is caused by individual ‘rogue’ landlords.”

What do you make visible?

Metaphor: “Wealth is being transferred upwards, tenants need to build power from below”. “Rent is a tax poor people pay to rich people for the right to live in society.”

Wording: Calling houses ‘homes’ not ‘properties’, and calling the money landlords make ‘profit’ instead of ‘income’.

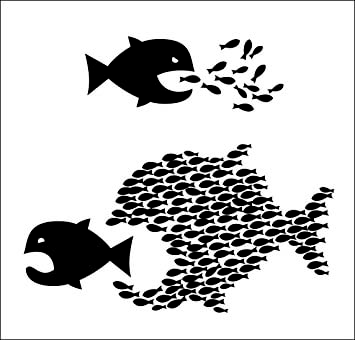

Images:

Different communication methods offer different kinds of engagement and will reach different segments of the spectrum of support. People also change their minds in various ways – through reading facts and figures, hearing personal stories, or experiencing something new. Enabling people to engage emotionally may be useful than bombarding them with information. Below are some tips on when to use different methods and how to maximise their impact.

Why use: Engaging with mainstream media is a useful way to reach the general population, inspire people to join your campaign, and put pressure on your opponents. There are also limits to what you can achieve through mainstream media, as the interests of media corporations will often be in opposition to the social change you are trying to make. Consider when it’s useful to engage with mainstream media, for example if you think there’s a good chance of sympathetic coverage or a strong opportunity to get your message across. Take advantage of moments when your campaign issue is in the public eye, like a major news story or an upcoming referendum.

Through mainstream media you are likely to reach people in every segment of the spectrum of support. This can be a good opportunity to target neutral people and passive opponents with a clear message that counters your opponent’s narrative. Thinking back to the Overton Window, there might be value in making a strong case for your vision even if you are opposed. It could be the first time someone has heard the issue framed in that way.

Tips: If you get an opportunity for mainstream media coverage, prepare 3 key messages you want to get across (think about the questions of structural power, your own power, and your vision). Consider visuals – what will come across in a few seconds of video footage or a single photograph? Anticipate how you could be opposed or misrepresented and plan how you will counter this.

Why use: If you are aiming to reach existing supporters, social media is useful for posting regular updates about your campaign activities and showing people how to get involved. It’s hard to reach beyond your ‘echo chamber’ on social media, but it does allow you to have complete editorial control. Stories are a great way of making an emotional impact and shifting passive supporters to active participants. Unlike the brief and limited information needed for mainstream media, social media allows the space to get stories across, as well as information and ideas that might build political analysis amongst your supporters.

Tips: Post regularly on your facebook or twitter page with updates from your campaign. Give details about upcoming meetings, actions and social events. Post photos regularly – these stand out more than text in a social media feed. You could also make short videos with footage of actions, or people in your group talking about the issue you’re fighting. Make posts that invite engagement, like asking your social media followers a question.

Why use: Face-to-face methods like door-knocking, stalls and public meetings are great ways to have two-way conversations and communicate by building relationships. Talking face-to-face allows you to tailor your message – for passive supporters by emphasising ways to take action, and for passive opponents by emphasising changing how they see the issue. These methods also allow you to systematically reach people affected by an issue – for example, door-knocking all the streets near to a local community centre that is being closed down.

Tips: Decide who you are trying to reach (e.g. ‘people who are already onside’ or ‘anyone who is a renter’), and plan how best to talk to them. Aim to spend the bulk of your time in conversations with those people, and keep other conversations short. Ask open questions and listen to where people are coming from. Face-to-face conversations can be like a ‘live’ reframing – offering a new way of seeing the issue. Try to challenge misconceptions or disagreements by highlighting structural power.

Talking face-to-face can also help passive supporters feel more empowered to take action with others. Have an upcoming meeting or action for interested people to get involved in after your conversation.

Why use: Flyers, posters and newsletters are a straightforward way to get across information and raise awareness about an issue. You can put posters up in the street, as well as local shops, community centres and pubs. Flyers can be posted through doors and given out to interested people at stalls, actions or doorknocking sessions. This allows people to learn more in their own time and gives them the space to take your arguments on board.

Tips: Printed materials are a great opportunity to put across your framing of the issue through punchy phrases, metaphors and images. You could include key facts or statistics – remember to keep these concise and clear. Posters should be eye-catching, with text someone can read in a few seconds. Include contact info or meeting times for your group on everything you print. Having a consistent style across your printed materials can make your campaign more recognisable, and producing reusable publicity that isn’t time-sensitive will reduce waste and costs.

Be creative! You could make badges and stickers, subvert advertising messages, create a film, or stage a banner drop. Design eye-catching banners that capture your message with a single phrase – imagine how it will come across in a photo of an action. Draw on the skills of people in your group and come up with inventive ways to get your message across.

Your messaging strategy is about more than simply what you say and the words you use. You can really increase your impact by planning how your different messaging activities will fit together, keep up momentum, and make use of opportunities. This plan ties together with your wider campaign strategy so that the messages you are putting out make the most of your campaign activities.

The ‘threshold effect’ describes the point at which your activities cut through and make an impact. It’s a useful way to understand how the spread of your activities will affect the impact your message makes.

Concentrating your messaging activities on a specific goal means you are more likely to break through the threshold where your message makes a difference. The same amount of energy distributed between lots of different goals is less likely to reach the threshold.

For example, informing people about all the potential problems related to fracking may mean that none of them really sink in. Try choosing just one (e.g. public health, or climate change) and then put it across in a range of different ways – through slogans, stories, images, fact-sheets and quotes in your press releases.

Thinking back to the Overton Window, significant events in society can shift the boundaries of ‘mainstream opinion’. In these moments, ‘radical’ ideas can seem sensible and appealing. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the status of ‘key workers’ suddenly changed when many low paid forms of work were recognised as important to keep society running. This presents a good opportunity to reframe how different kinds of work are valued in society, and push for demands like a pay rise for healthcare workers. Think about how your campaign messaging can make the most of key opportunities, and help make these temporary shifts more permanent.

Letting people know about your campaign successes is important to maintain momentum and inspire new people to action. Put out updates about victories big and small. Celebrate wins with social events where new supporters can meet people and get involved.

Organise your messaging activities so that they build momentum and bring people with you as the campaign grows. For example, going door-knocking in the weeks leading up to a public meeting gives you something to invite people to at the end of your conversation. Putting a press release in the local paper after a big action may bring new people to your meetings and events.

Each time you do an outreach activity, think about how it will feed in to the next thing you’ve got planned. Imagine you are a new person hearing about the campaign, and think about the upcoming opportunities you would have to get involved. Emphasise these in your outreach.

Campaign against a new coal mine, messaging strategy focused on outreach to local people.

What is the injustice: The new coal mine will contribute to climate change, pollute the local environment, exploit workers and damage people’s health.

What is the structural power: Extraction for profit, by fossil fuel corporations and the state.

Who is affected and what is their source of power: Local people, who have the power to disrupt the mine through collective action. Potential workers, who have the power to collectively refuse their labour.

Your vision: End of fossil fuels. Sustainable green jobs, shared wealth and participatory democracy. Clean air & green spaces.

Opponent’s narrative: “The new coal mine will power thousands of homes and create hundreds of desperately needed jobs in the area.”

Counter narrative: “A new coal mine would pollute our air and water, exploit workers and contribute to catastrophic climate change, all to profit corporations. We need renewable energy instead to protect ecosystems and empower workers with well paid jobs for the future. We have the power to stop the mine and decide what we want for our community.”

Metaphors: ‘No pollution for profit: green jobs now!’ ‘We won’t let corporations extract from our communities.’ ‘Power the future for people and planet.’

Wording: ‘Climate justice’ instead of ‘protecting the environment’. ‘Living ecosystems’ instead of ‘earth’s resources’.

Images: Images that highlight the power of collective action.

Reaching local people: Door-knocking residents with a petition. Holding a weekly stall in the town centre with leaflets to hand out. Posters up in streets, shops and pubs. Public meeting with information and local speakers. Emphasis on your collective power, and vision for the future of the community.

Reaching potential supporters (e.g. sympathetic environmentalists): Regular social media updates on campaign activities and wins. Emphasis on ways to take action.

Wider messaging: Press releases with major actions. Radio interviews. Emphasis on countering opponent’s narrative and shifting Overton window.

Weekly stalls and regular door-knocking sessions building towards a public meeting after several weeks. Big outreach push prior to planning application objections. Group actions and press releases timed to apply pressure on council meetings.